Cindy & Beth

A mother’s love; a daughter’s journey

Cindy West Rigsbee, clad in a purple short-sleeve shirt, purple leggings and sparkly purple shoes, walks hand-in-hand with her 46-year-old daughter, Beth, through the doors of Duke Cancer Center in Durham, N.C.

Cindy has walked through the same glass doors every two weeks for the past eighteen months — ever since she received a terminal, stage four pancreatic cancer diagnosis in January 2023. The chemotherapy drugs have sapped her energy, upset her stomach and numbed the feeling in her fingertips, but so far, they’ve kept her alive.

Today will mark another CT scan. Another day of immense uncertainty. And for the first time, Cindy’s daughter will be here to see it.

Beth follows her mom into the exam room and takes a seat in the chair next to the door. She peeks her head around the corner of the machine to watch as the nurses help her mother onto the table and insert a needle into her arm through which to administer fluids.

“That’s my mama,” Beth tells the nurses. “I love her.”

When Cindy is ready to be rolled into the machine, the nurses tell Beth to step outside.

“No,” Beth tells them, shaking her head like a young child.

Eventually, with some coaxing, she follows them out of the room.

Beth watches Cindy prepare for a CT scan at Duke Cancer Center on Oct. 20, 2023.

For nearly all of Beth’s life, Cindy has shouldered the dual role of mother and caregiver. Beth’s daily seizures and chronic nausea required around the clock care, and Cindy stepped in to provide it. No one knew Beth quite the way she did.

But when Cindy was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and told she had at most two years to live, she was forced to consider what Beth’s life would look like after her death.

“If you don't have [a plan], what's going to happen to your children?” Cindy says she asked herself. “What's going to happen to your young special needs adults?”

Beth watches Cindy water her garden outside the front of their home in Durham, N.C. on July 26, 2023.

Beth eats breakfast Cindy cooked on July 27, 2023.

Beth talks on the phone with her boyfriend.

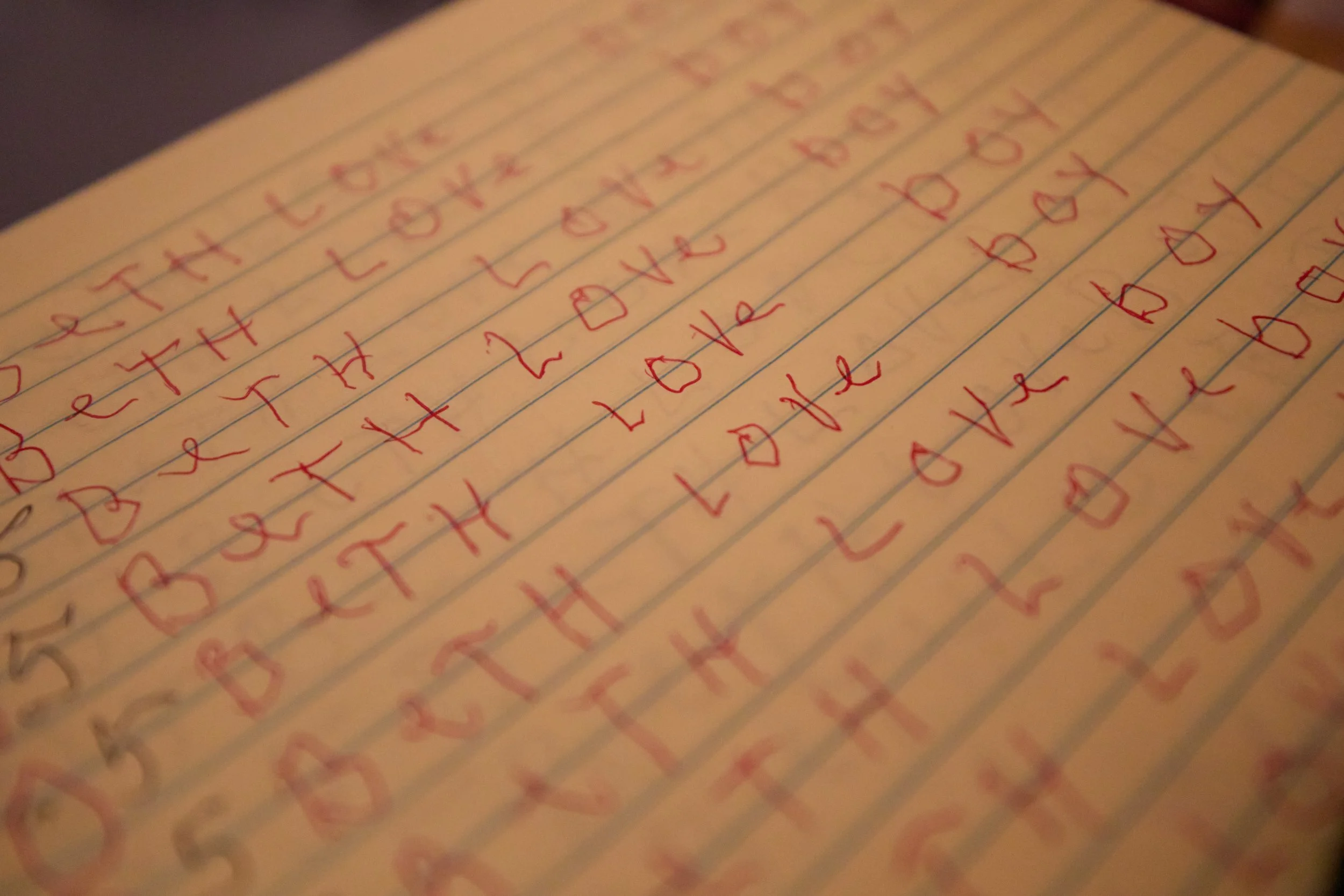

Beth writes about boys in one of her notebooks. “Beth always goes for the bad boys, not the ones we like,” Cindy said, smiling at Roger.

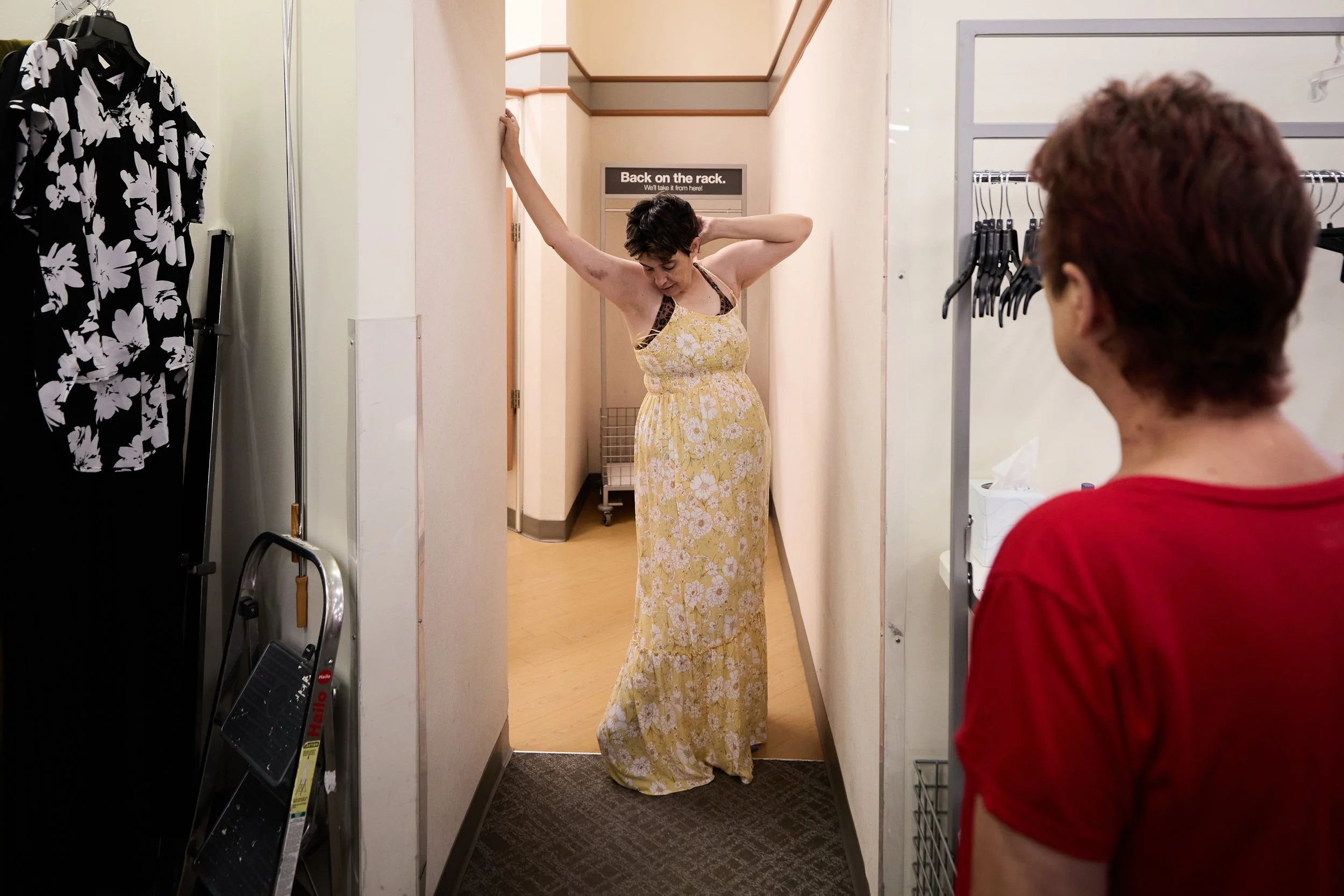

Beth tries on a summer dress at Kohl’s for an upcoming dance while Cindy watches on.

Beth was 18 months old when Cindy first noticed something was different.

Cindy was rocking Beth to sleep when Beth’s tiny arms jerked to the side. Moments later, Beth’s eyes went blank, and her arms jerked again.

“This isn’t normal,” Cindy thought.

The neurologist confirmed Cindy’s suspicions. Her daughter had a rare form of epilepsy called Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome, or LGS.

About three million Americans are living with epilepsy, of which half a million are children. Just 2-5% of children with epilepsy are diagnosed with LGS. Symptoms usually appear before age 5, and include multiple types of seizures, behavior challenges and delayed brain development.

“I had no idea that it would end up being as bad as it was,” Cindy remembers thinking.

By age 5, Beth was experiencing 60 seizures a week.

The seizures usually lasted several minutes. Beth stared into space, unable to communicate. Sometimes, she experienced extreme muscle contractions, and even lost consciousness.

“It was like an invisible person would just slam her to the floor,” Cindy remembered.

They tried every medication Beth’s neurologist could think of. For weeks at a time, Beth lived in the hospital. Cindy and her husband, Roger, traded shifts staying with their daughter; if she was left alone, doctors locked Beth in a covered, cage-like bed to protect her from hurting herself during further seizures.

Nothing the doctors tried could stop Beth’s seizures.

During one particularly severe seizure, Beth split her lip open, requiring stitches. Roger drove her to the hospital. As he drove down the interstate, he turned to his faith.

“I was cursing God and begging God at the same time,” Roger said. “I didn’t know that's possible. But it is. Because she’s just so helpless.”

As time passed, Cindy and Roger slowly settled into their own kind of normal.

Beth attended special needs classes during the day, while Cindy and Roger both worked full time jobs. On the weekends, Beth took therapeutic horseback riding lessons and participated in Special Olympics cheerleading classes. Beth’s teachers and other parents in her classes slowly helped the Rigsbees figure out how to navigate the system of governmental support.

But when Beth turned 21 and graduated from high school, Cindy and Roger’s normal suddenly changed.

In the absence of school, and unable to work a job, Beth spent her days at home – and with full time jobs, Cindy and Roger were ill equipped to provide Beth the 24/7 care she needed.

“There was a big gap [in support],” Cindy said. “Like, Where’s she got to go? What's she going to do?”

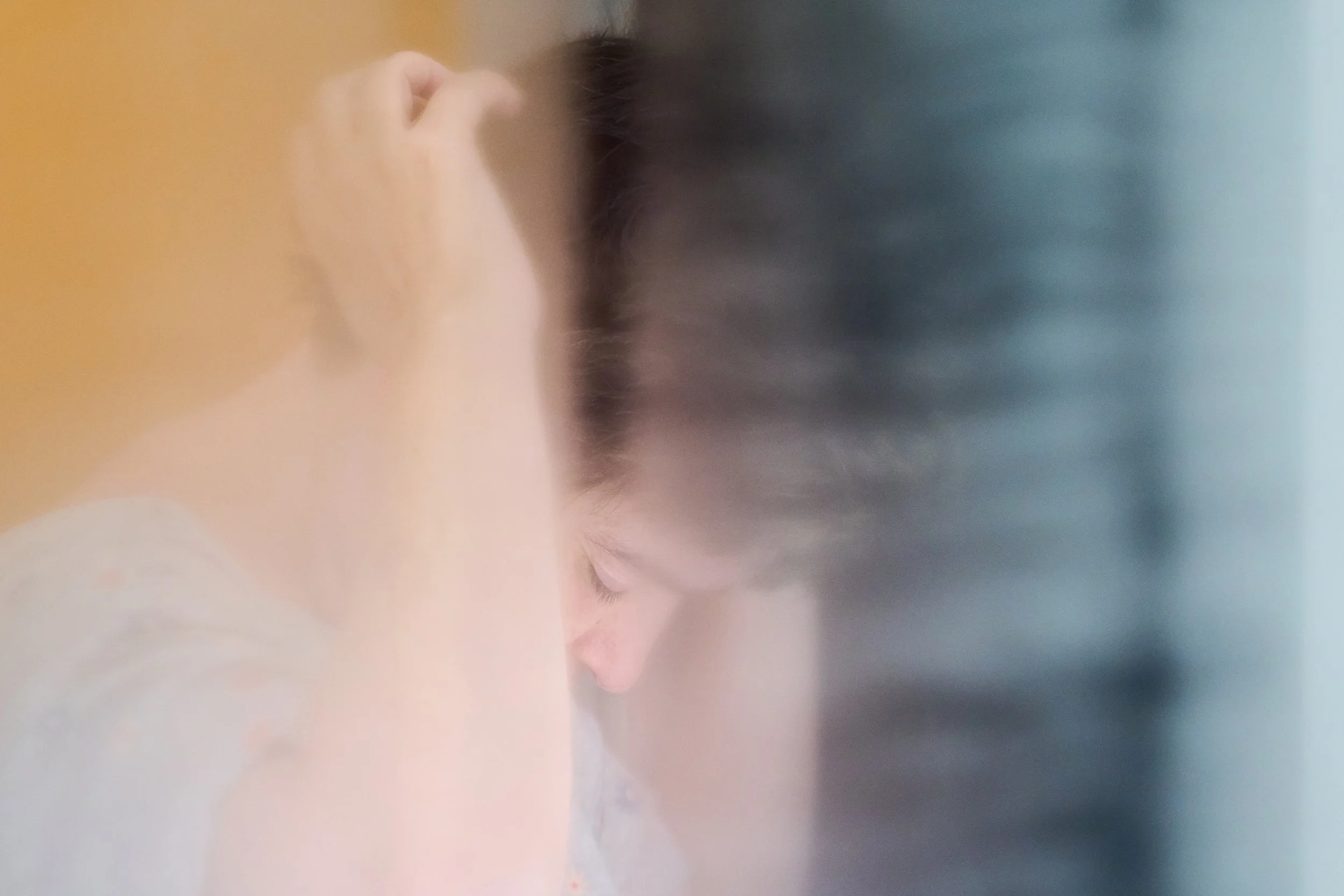

Beth’s face is reflected in a mirror after a shower. Beth continues to experience 3-4 seizures a day.

According to the most recent data from the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, nearly 200,000 adults in North Carolina are living with intellectual/developmental disabilities (I/DD). Like Beth, just over half of these adults live at home with their parents or relatives.

Beth’s ability to live at home comfortably has largely been made possible by the support she receives through the NC Innovations Waiver, a program of Medicaid. Families who successfully apply for a waiver become eligible for government-sponsored case management support, home health aides, personal care, adult day health services, habilitation (both day and residential) and respite care.

But receiving a waiver isn’t a quick step-by-step process.

In order to apply for a waiver, families must submit a lengthy application and go through an eligibility screening process. Then, they have to wait —on average 8-10 years. In North Carolina, nearly 19,000 people are currently on the waitlist for waivers.

“It's easier to get someone a lot of times into a group home,” Cindy said, “than it is to try to get services so that they can stay home.”

Beth and her best friend, Neema, sing karaoke in Beth’s living room. Cindy and the Rigsbee’s dog, Koal, joined in.

Cindy helps Beth get ready for the Night to Shine Prom, a dance for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities hosted by Reality Ministries, at their home in Durham, N.C. on Feb. 23, 2024. Dancing is one of Beth’s favorite activities.

Access to an Innovations Waiver does not guarantee care; Cindy says the ability to access services often depends on a family’s ability to advocate for them.

“It’s almost like you need to be a lawyer to understand [the system],” Cindy explains.

The Rigsbees waited eight years before receiving a waiver for Beth. One of the largest benefits of the Innovations Waiver to the Rigsbee family has been the sponsored support from Direct Support Professionals (DSPs): working caregivers who provide one-on-one support for Beth at the Rigsbee’s home.

Over the next two decades, the Rigsbees relied on DSPs to fill the gaps in care that they could not provide while working full-time jobs. But during the COVID-19 pandemic, all at-home services were put on pause.

When the services were finally resumed, many caregivers, fed up with being paid near-minimum wage, had found other positions.

Cindy’s terminal cancer diagnosis coincided with the growing shortage of caregivers. For the first year after her diagnosis, she repeatedly called her service agency to ask for help, and said she continually received the same response: they were “working on it.”

In the absence of DSP support, with Roger still working full time, Cindy shouldered the added burden of care, driving Beth to her social activities and doctor’s appointments in between chemotherapy and doctor’s appointments.

When government options leave gaps in care, others step in.

Reality Ministries is one example.

Beth and her friend, Kayla, who also attends Reality Ministries, try on fireman’s uniforms at the Special Olympics horse show in Tryon, N.C. The truck was brought to allow the athletes the chance to see what it was like being a firefighter.

Beth prepares for a horseback riding lesson at Bright Star Stables in Rougemont, N.C.

Beth rides the carousel at the Special Olympics horseback riding show in Tryon, N.C.

“Reality” is a non-profit organization based in Durham, N.C., that serves between 250 and 350 adults of all abilities across the Triangle. Adults can participate in activity groups, home groups and community worship.

Reality has become an anchor in the Rigsbees’ lives.

“Morning Mingle” — a Monday morning activity through Reality Ministries — gives Beth the chance to go socialize with other adults with disabilities. She often says it’s the highlight of her week.

At “Morning Mingle”, Beth has met a group of women she now calls her “sisters.” They regularly have sleepovers on the weekends and go to bingo together.

In addition to Morning Mingle, Beth regularly attends community groups at Reality, and participates in a monthly Rock Climbing club and drama group. She also participates in Reality’s annual Night to Shine Prom, performs in their annual Talent Show and goes with Cindy to Reality’s annual overnight retreat in the mountains with her friends.

Reality Ministries has given the Rigsbees a community of other families with similar experiences — something they struggled to find when Beth was growing up.

Following Cindy’s cancer diagnosis, a group of Reality families set up a meal train to deliver food to the Rigsbee’s house once a week. They’ve also cared for Beth while Roger drives Cindy to and from chemotherapy – a necessity in the absence of DSP support.

“Cancer's a disease that not only affects the person that has it, but all those around you that love you,” Cindy said. “I can't go out and do the things that I used to do; I’m doing good if I can walk to the car. I hate to see all the pain and suffering that it does to the people that you love.”

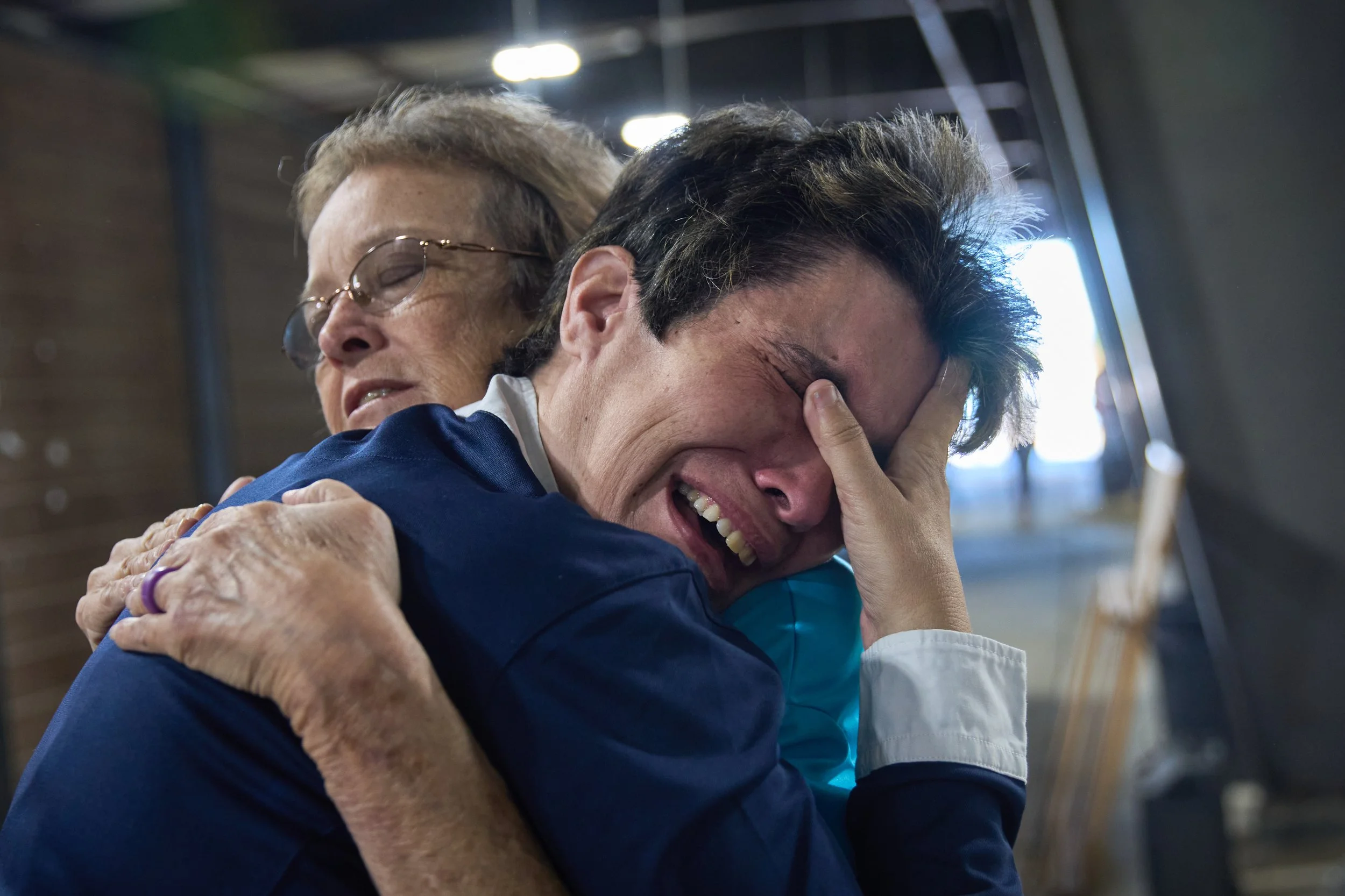

Cindy embraces Beth after she fell and hurt herself during the Special Olympics horse show in Tryon, N.C.

Cindy looks out the window during a chemotherapy session at Duke Cancer Center.

Cindy pauses for a moment while tending to her garden on Friday, June 26, 2023.

Cindy and Beth get ready for bed on July 26, 2023. They’ve shared a bedroom for more than a decade.

Roger takes a nap while Cindy receives chemotherapy at Duke Cancer Center. Cindy stays wide awake, an electric heating blanket wrapped around her.

The uncertainty for the future perhaps weighs most heavily on Roger.

Cindy and Roger met when they were teenagers. They fell in love, eloping to South Carolina a year after they met. Not long after that, when Cindy was 21 years old, she got pregnant with Beth. The two have been each other’s support ever since.

The uncertainty for the future is something Roger finds “hard to bear” — particularly when it comes to Beth.

“I can never — I mean, I can be the best father I can be — but I can never be her mother,” Roger says.

In February 2024, Roger chaperoned Beth to a dance. In the middle, Beth had a seizure, causing her to wet her pants. Roger took Beth to the restroom, and while she changed, Roger waited outside.

A few minutes later, Beth emerged from the bathroom naked. Still in a trance from her seizure, she had forgotten to put on her new clothes. Roger burst into tears.

“How am I going to make it?” Roger remembers asking himself. “I'm not going to be a mother and a father to Beth. I'm not going to do everything [Cindy] does.”

Cindy and Beth raise their hands for the judge during a hearing to arrange standby guardianship with Roger for Beth on Friday, July 12, 2023 at the Durham Courthouse. “It’s bittersweet,” Cindy said as she walked out of the room.

When Cindy’s doctor told her it was time to start arranging for a future without her, she began calling her family and friends. She found a lawyer to help her with her will, and scheduled a court date to arrange standby guardianship with Roger for Beth.

Roger and Cindy were married, but had briefly divorced in the 1990s, during which time Cindy had gained full custody of Beth.

The day the Rigsbees went to court, Roger sat on one side, Beth and Cindy on the other. When the judge finished the paperwork, Cindy hung her head. Across the room, Beth embraced Roger with a smile.

“It’s bittersweet,” Cindy said as she walked out of the courtroom.

When asked what she’d meant, Cindy had to hold back tears.

“She's my daughter that I've cared for for all these years, and I didn't want to lose that,” Cindy said. “But I know her Daddy loves her, so I have to not think about what's best for me, but I have to think about what's best for Beth.”

Despite the oncologist’s predictions, Cindy’s scans over the next few months continued to show good news: her tumors had remained stable.

There was no need to worry Beth yet, Cindy told herself.

But one July morning, Beth walked up to Roger.

“I don’t want mama to go to heaven,” Beth told her dad.

Beth hangs her head while sitting in the garage on Friday, June 26, 2023.

Beth stands on the Rigsbee’s front porch in the waning evening light.

Cindy’s tumors remained stable for the first year-and-a-half after her initial diagnosis. They weren’t shrinking, but they weren’t growing, either. By May of 2024, both Cindy and her oncologist were feeling optimistic.

That summer, Cindy decided to enroll in a trial treatment. It was risky, her oncologist told her, but if it worked, it would give Cindy the greatest chance at slowing the growth of her tumors.

In August 2024, Cindy suffered a stroke that landed her in the emergency room. There, doctors discovered the tumors had spread to her hip, low back and brain.

Less than a month later, on September 19, Cindy entered the ICU.

Cindy reaches out to kiss Beth in the ICU on Thursday, Sept. 19, 2024.

Cindy was admitted to the ICU on a sunny Thursday morning. By the afternoon, it had started to rain, and doctors doubted she would make it through the day.

Roger holds Cindy’s hand as she sleeps in the ICU on Thursday, Sept. 19, 2024.

Roger said it felt like losing a part of his soul. Beth said she didn’t want Mama to pass away. And while Cindy lay in the hospital bed sleeping, her brother Mike, joked that she sounded like a “mad cat.”

Roger gives Cindy a kiss on the forehead while she sleeps in the ICU on Thursday, Sept. 19, 2024.

At 3:33 a.m. on Saturday, September 21, 2024, Cindy took her final breath. Over the sixty hours she spent in the hospital, numerous friends and family came by to say their goodbyes.

The next day, dozens of friends and family packed the room for her funeral service at Reality Ministries in Durham, N.C., filling the space with music and stories. Roger passed along Cindy’s wish to those in attendance: instead of flowers, make donations in her honor to Reality Ministries.

Beth opened the service with a song, then came to stand in the back of the room as Roger prepared to give his eulogy.

“Only 25% of pancreatic cancer patients make it two years after their diagnosis,” Roger remarked. “Cindy made it almost 25 months. She wanted to live. I wanted her to live.”

Beth sings a song in honor of Cindy during a memorial service at Reality Ministries in Durham, N.C. on Sunday, Sept. 22, 2024.

In the months following Cindy’s death, Beth continued her weekly routine at Reality Ministries, and Roger was able to continue part-time work thanks to the help of caregivers provided through their Innovations Waiver.

“We’re doing well. Some good days, some sad days,” Roger wrote in a text in November. “The pain of losing her is almost unbearable at times. At times, I’ll have a question that Cindy could answer and I realize once more she’s not here. But Beth and I will make it! We have to. Cindy depended on me for that.”

Month by month, Roger and Beth slowly figured out how to move forward.

“Daily we each remember out loud that Cindy continues to love and live in our hearts. But we surely do miss her and always will!” Roger wrote in March 2025. “And life slowly moves on. We are both learning to live a new reality. And we have our fur babies that provide plenty of love.”

On a sunny spring day in May 2025, Beth and her direct support professional, Lessie, sit on the couch in the Rigsbees living room. Roger rests in a chair across the room. Their three dogs — two miniature poodles and one regular-sized poodle — bound between them, using the couches and chairs like an obstacle course.

It’s been eight months since Cindy passed, and one month since her first heavenly birthday.

In the entryway to their home, Roger has lined five shelves with purple velvet, the color of pancreatic cancer awareness and Cindy’s favorite. Photos fill the wall: Cindy and Beth horseback riding at the beach, Cindy cradling Beth as a tiny baby, Cindy and Roger falling in love as teenagers. There are too many photos to arrange them in a singular line, so Roger has stacked the smaller ones in the corners of the larger frames, creating a kind of homemade collage of their 49 years together. On the second shelf rests a heart-shaped urn, engraved with Cindy’s name, that glows bronze in the afternoon light.

Tucked away in the back of the third shelf reads the following plaque:

May the winds of heaven

blow softly and whisper in your ear

how much we love and miss you

and wish that you were here.

Cindy and Beth smile for the camera with their dogs Lucy and Koal in June 2023.

Author’s Note

How do you prepare for someone to die?

I asked myself this question numerous times throughout this project, knowing rationally that there was no way to prepare, but asking myself nonetheless — perhaps as a way to avoid the pain I knew was coming, and was sometimes already there.

I initially approached this project as a documentary journalist: trying my best to write down what I witnessed without inserting myself into the story.

But as time went on, and my relationship with the Rigsbees deepened, I found myself unable to separate my own feelings and experiences from the project itself.

What the Rigsbees have done in sharing their story, I hope, is make it so no one in their position feels like they have to walk this road alone. To care and to be cared for, the Rigsbees have taught me, is at the very core of what it means to be human.

I hope you feel the gift of the Rigsbees’ courage and vulnerability in sharing their story as deeply as I have.

In loving memory of Cindy West Rigsbee, without whom I would not be the person or photographer I am today. Thank you to the Rigsbee family for welcoming me into your lives. The impact you’ve made is greater than you know.